We’re always told that the journey is just as important as the destination. This is true in many aspects of life, but perhaps nowhere as much as in scientific research. Flexibility, curiosity, and attention to detail can lead to a treasure you weren’t even expecting to find. TAU’s scientists talk about research that began one way and ended another, thanks to a few surprises along the way.

A treasure in a pot

A team of archeologists on an excavation mission found that sometimes, the appearance of a clay pot is no indication of its contents. “On one of the excavations in Megiddo, we removed the partitions separating the different sections of the dig and found a whole clay pot full of dirt,” says Naama Walzer, a doctoral student in the

Department of Archeology and Early Eastern Cultures at Tel Aviv University.

“We packed it up and planned to send it to a molecular residue lab to find out what used to be stored inside of this pot, which we dated to around 1100 BCE.” The pot was stored in an office, but after a while it became clear that preservation in that area of the excavation wasn’t up to standard, so the team decided to empty the pot, in a controlled way, and poured out its contents on the table. “We weren’t expecting to find what ended up being inside: a treasure trove of jewelry, considered one of the greatest troves found in Israel from the Biblical period!”

The pot discovered in Megiddo. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

The pot discovered in Megiddo. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

Among other things, the trove contained nine large earrings and a seal ring, over a thousand small gold beads, and silver necklaces and jewelry. “This is how we found the big treasure of Area H, which is now part of the permanent exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem,” concludes Walzer.

Earrings, rings and gold beads. A huge treasure from the Biblical period. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

The longest record in the lowest place

Earrings, rings and gold beads. A huge treasure from the Biblical period. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

The longest record in the lowest place

We’ve all heard that still water runs deep, but did you know it can run deep enough to be remembered hundreds of thousands of years later? “I was looking for places to sample a rock that sank, in a still setting, to the bottom of the Dead Sea,” recalls Prof. Shmulik Marco, head of the

Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences.

“The goal was to measure the magnetic properties of the rock in order to reconstruct the changes that have occurred in the Earth’s magnetic field. This information is essential to understanding one of the most important mysteries in geology. Scientists still have no satisfactory explanation for the mechanism that causes changes in the magnetic field, such as surprising reversals or constant changes in the position of the magnetic poles. While sampling the rocks, I found layers that looked “messy”. The study took an unexpected turn when I realized the “mess” was the result of earthquakes, and that became the main focus of the research.”

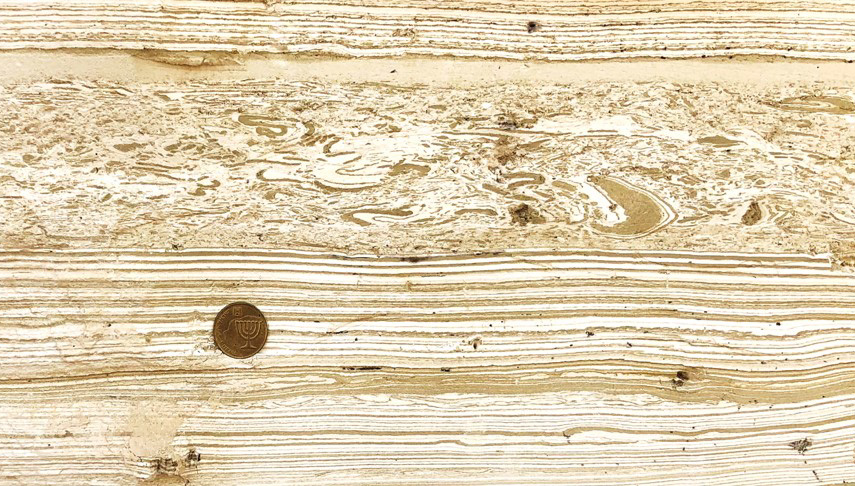

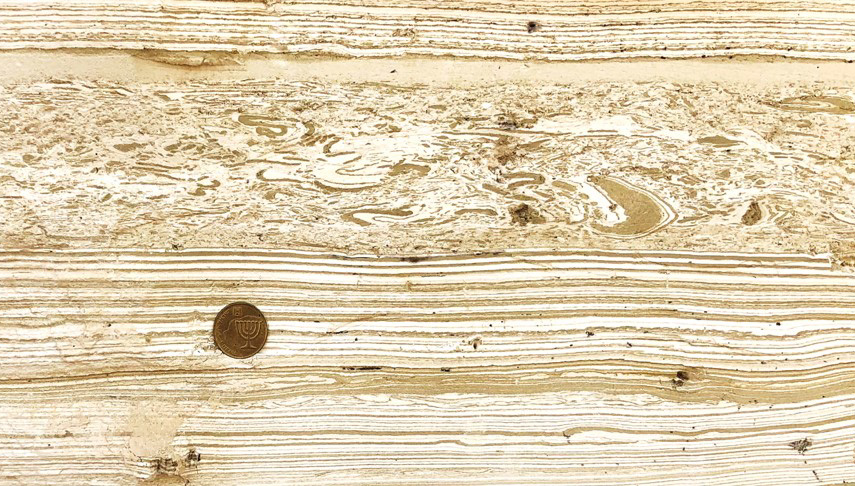

The lowest place: layers of rock at the Dead Sea

The lowest place: layers of rock at the Dead Sea

Because modern seismographs have only existed for about a century, which is barely a moment in earthquake terms, it’s impossible to know how a specific area behaves over long periods of time. In Israel, for example, there’s documentation from the Biblical period (about 3,000 years ago), which is still considered very little. “But now we have a record of the earthquakes that happened around the Dead Sea in the last 220,000 years. That’s considered a unique, world record, because there’s no other documentation in the world that’s so long and continuous,” concludes Professor Marco.

Neat vs messy: A layer of rock in which the natural order was disturbed

A miracle of light

Neat vs messy: A layer of rock in which the natural order was disturbed

A miracle of light

As she was nearing the end of her postdoctoral studies at Yale University, Dr. Ines Zucker of the

Iby and Aladar Fleischmann Faculty of Engineering decided to advise an undergraduate student in a promising, short-term study.

But as we all know, the only thing you can count on in life is that everything changes: “The purpose of the study was to show a difference in damage to liposomes (microscopic spheres filled by fluorescent fluid and surrounded by a membrane, used in medicine and in scientific studies of biological membranes) by a nanomatter called MnO2, produced in various structures,” explains Dr. Zucker.

“In the past, we’ve shown a fluorescent fluid leak (i.e., liposome damage) was dependent on the surface of the nanomatter, and this time we wanted to show it also depended on its structure. But… research has its own rules – we couldn’t find the kind of damage we were looking for. Right as we were about to give up on the study, we took the system to a fluorescence microscope, where we saw that the liposomes and the nanomatter interact in a way we’ve never seen before in this context: the liposomes envelop the nanomatter, but remain whole, intact spheres without leakage! It was like a miracle of light.”

“Many times unexpected discoveries surprise us.” Dr. Zucker in the lab

A star (re)born

“Many times unexpected discoveries surprise us.” Dr. Zucker in the lab

A star (re)born

For Dr. Iair Arcavi, of the

Department of Astrophysics at the

Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, a routine evening of surveying space through a robotic telescope led to discovering a brand new phenomenon: the resurrection of a star.

“A few years ago, we came across a ‘star that didn’t want to die’ and kept exploding again and again,” Dr. Arcavi says. “Every night the telescope would find lots of new things, most of them uninteresting. Even with this supernova (which is a star that exploded), we initially thought it was uninteresting, because when the survey first caught it, it was in the dimming stage, and we thought we’d missed the interesting part. We noticed for weeks that the supernova was starting to get bright again, which is something that shouldn’t happen, so that piqued our interest and made us follow the supernova with additional telescopes.”

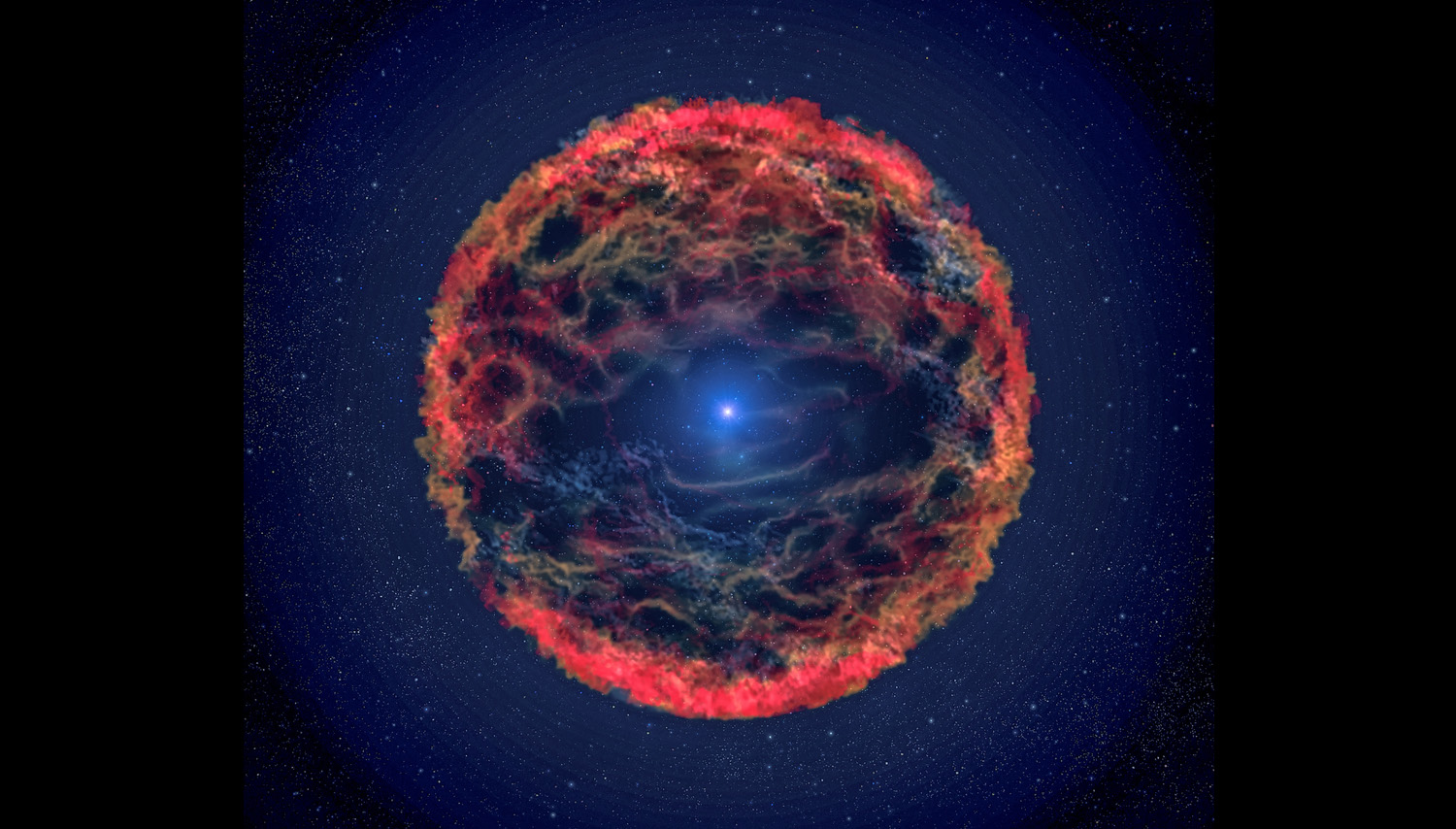

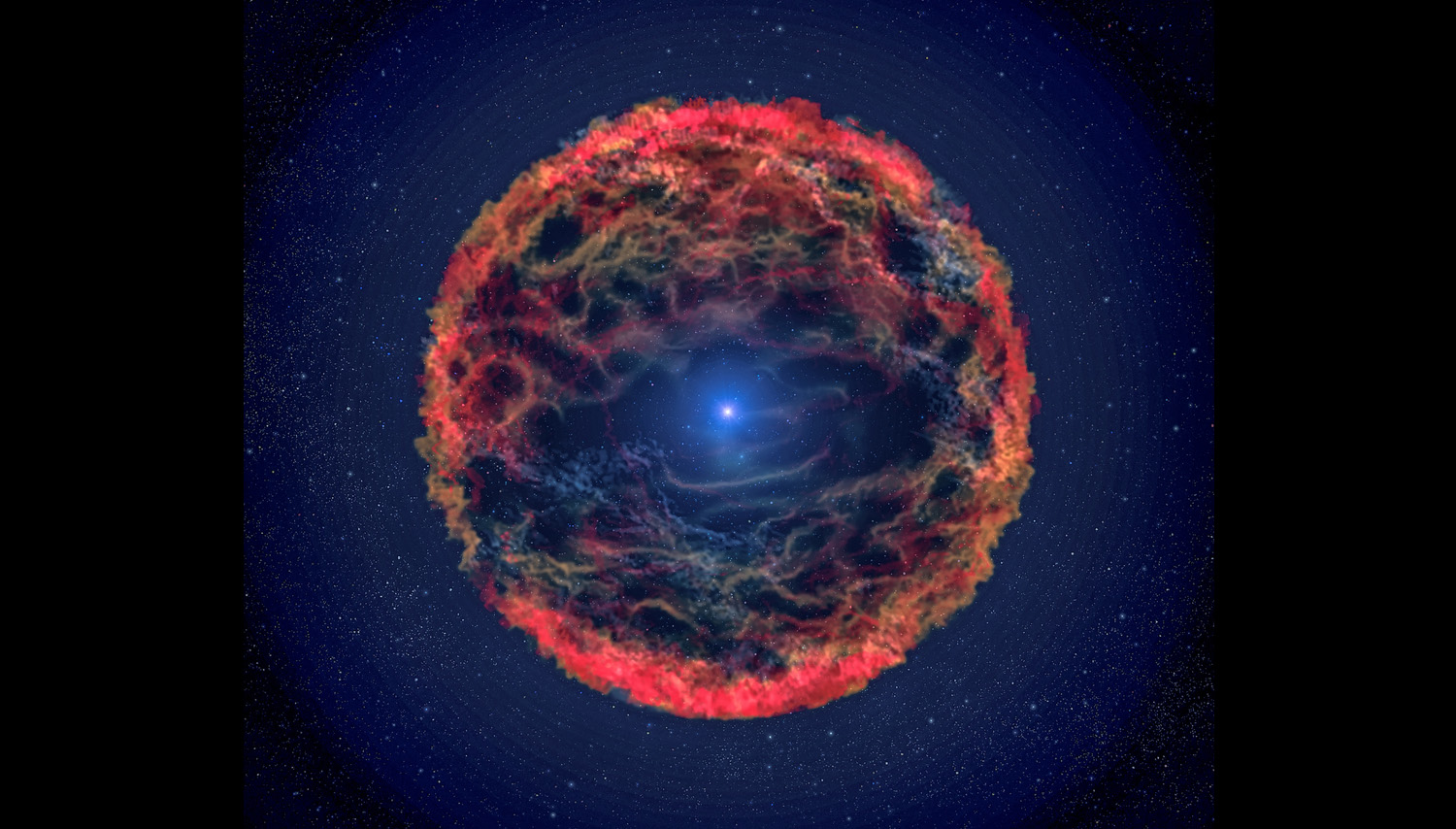

A supernova exploding far, far away

A supernova exploding far, far away

“Usually, when a star explodes, the light intensity goes up and down and eventually disappears after a few months. In our case, the light intensity went up and down, then did it again and again, for a total of five times over two years. What surprised us even more was when we discovered that this star actually exploded in 1954, and after a star explodes, it’s not supposed to explode again, because the explosion destroys the star. To this day no one’s been able to explain it, and we haven’t seen a similar event since.”

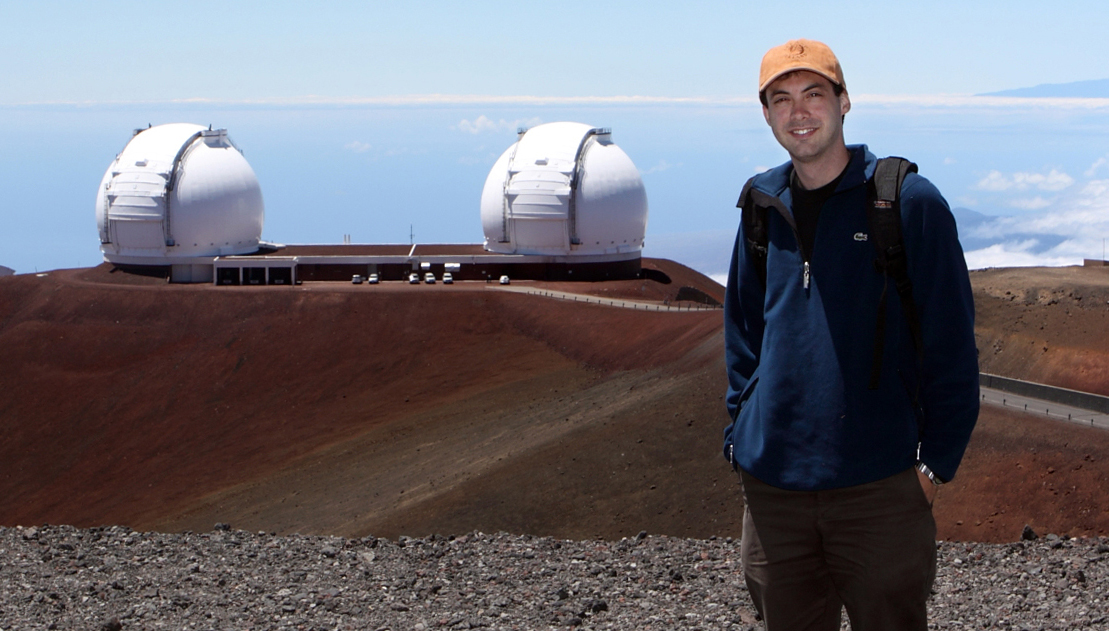

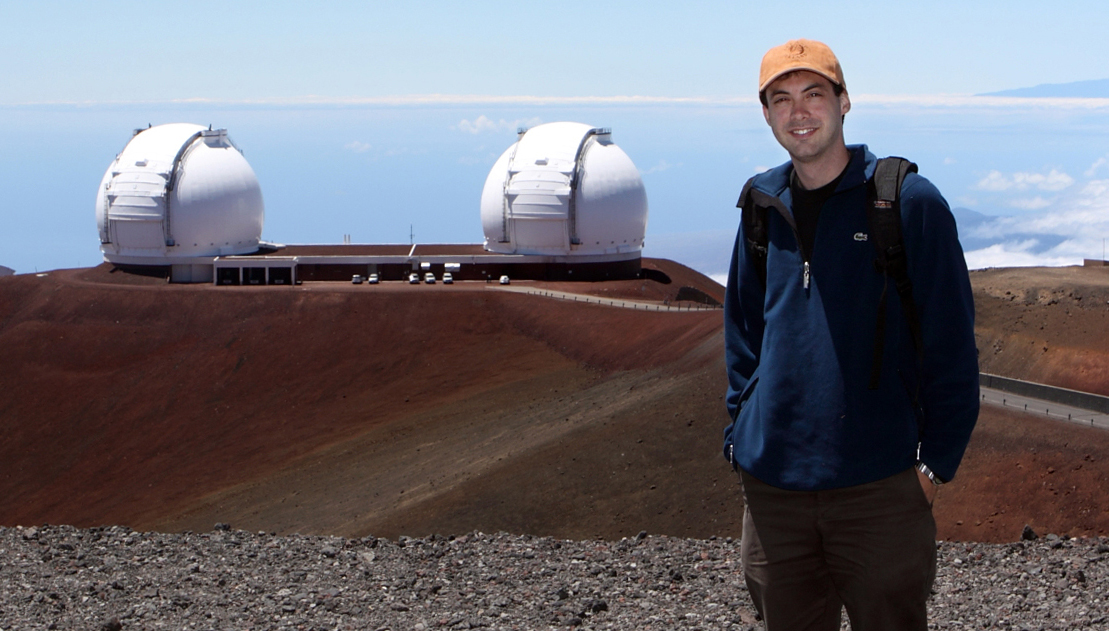

The sky is full of surprises: Dr. Arcavi and the Hawaii observatory

Two for the price of one

The sky is full of surprises: Dr. Arcavi and the Hawaii observatory

Two for the price of one

Have you ever looked for a solution to a problem, only to solve an entirely different problem along the way? That’s exactly what happened to Prof. Noam Shomron of the

Sackler School of Medicine.

“We wanted to develop a way to identify a specific disease, but along the way we discovered more options, so we made those additional targets of the research,” he says. “We tracked thousands of pregnant women, to characterize blood molecules that can be early markers of preeclampsia, a condition that can only occur after the 20th week of pregnancy. Not only did we find those molecules, we also managed to characterize other molecules, that could be an indicator of gestational diabetes.” (There’s no connection between the two conditions, except that they both occur during pregnancy.)

“What’s exciting about this story is that there’s still no way of identifying, in the first trimester, using a simple blood test, problems that can occur in the second or third trimester. But our discovery will allow simple blood tests to be developed to identify both conditions, which will then lead to preventative measures at an early stage, and ensure the wellbeing of both mother and baby.”

Professor Shomron talking about his accidental discovery at an “Atnahta” event at TAU

Professor Shomron talking about his accidental discovery at an “Atnahta” event at TAU

The pot discovered in Megiddo. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

Among other things, the trove contained nine large earrings and a seal ring, over a thousand small gold beads, and silver necklaces and jewelry. “This is how we found the big treasure of Area H, which is now part of the permanent exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem,” concludes Walzer.

The pot discovered in Megiddo. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

Among other things, the trove contained nine large earrings and a seal ring, over a thousand small gold beads, and silver necklaces and jewelry. “This is how we found the big treasure of Area H, which is now part of the permanent exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem,” concludes Walzer.

Earrings, rings and gold beads. A huge treasure from the Biblical period. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

The longest record in the lowest place

We’ve all heard that still water runs deep, but did you know it can run deep enough to be remembered hundreds of thousands of years later? “I was looking for places to sample a rock that sank, in a still setting, to the bottom of the Dead Sea,” recalls Prof. Shmulik Marco, head of the Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences.

“The goal was to measure the magnetic properties of the rock in order to reconstruct the changes that have occurred in the Earth’s magnetic field. This information is essential to understanding one of the most important mysteries in geology. Scientists still have no satisfactory explanation for the mechanism that causes changes in the magnetic field, such as surprising reversals or constant changes in the position of the magnetic poles. While sampling the rocks, I found layers that looked “messy”. The study took an unexpected turn when I realized the “mess” was the result of earthquakes, and that became the main focus of the research.”

Earrings, rings and gold beads. A huge treasure from the Biblical period. (Photo courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Archeology Institute)

The longest record in the lowest place

We’ve all heard that still water runs deep, but did you know it can run deep enough to be remembered hundreds of thousands of years later? “I was looking for places to sample a rock that sank, in a still setting, to the bottom of the Dead Sea,” recalls Prof. Shmulik Marco, head of the Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences.

“The goal was to measure the magnetic properties of the rock in order to reconstruct the changes that have occurred in the Earth’s magnetic field. This information is essential to understanding one of the most important mysteries in geology. Scientists still have no satisfactory explanation for the mechanism that causes changes in the magnetic field, such as surprising reversals or constant changes in the position of the magnetic poles. While sampling the rocks, I found layers that looked “messy”. The study took an unexpected turn when I realized the “mess” was the result of earthquakes, and that became the main focus of the research.”

The lowest place: layers of rock at the Dead Sea

Because modern seismographs have only existed for about a century, which is barely a moment in earthquake terms, it’s impossible to know how a specific area behaves over long periods of time. In Israel, for example, there’s documentation from the Biblical period (about 3,000 years ago), which is still considered very little. “But now we have a record of the earthquakes that happened around the Dead Sea in the last 220,000 years. That’s considered a unique, world record, because there’s no other documentation in the world that’s so long and continuous,” concludes Professor Marco.

The lowest place: layers of rock at the Dead Sea

Because modern seismographs have only existed for about a century, which is barely a moment in earthquake terms, it’s impossible to know how a specific area behaves over long periods of time. In Israel, for example, there’s documentation from the Biblical period (about 3,000 years ago), which is still considered very little. “But now we have a record of the earthquakes that happened around the Dead Sea in the last 220,000 years. That’s considered a unique, world record, because there’s no other documentation in the world that’s so long and continuous,” concludes Professor Marco.

Neat vs messy: A layer of rock in which the natural order was disturbed

A miracle of light

As she was nearing the end of her postdoctoral studies at Yale University, Dr. Ines Zucker of the Iby and Aladar Fleischmann Faculty of Engineering decided to advise an undergraduate student in a promising, short-term study.

But as we all know, the only thing you can count on in life is that everything changes: “The purpose of the study was to show a difference in damage to liposomes (microscopic spheres filled by fluorescent fluid and surrounded by a membrane, used in medicine and in scientific studies of biological membranes) by a nanomatter called MnO2, produced in various structures,” explains Dr. Zucker.

“In the past, we’ve shown a fluorescent fluid leak (i.e., liposome damage) was dependent on the surface of the nanomatter, and this time we wanted to show it also depended on its structure. But… research has its own rules – we couldn’t find the kind of damage we were looking for. Right as we were about to give up on the study, we took the system to a fluorescence microscope, where we saw that the liposomes and the nanomatter interact in a way we’ve never seen before in this context: the liposomes envelop the nanomatter, but remain whole, intact spheres without leakage! It was like a miracle of light.”

Neat vs messy: A layer of rock in which the natural order was disturbed

A miracle of light

As she was nearing the end of her postdoctoral studies at Yale University, Dr. Ines Zucker of the Iby and Aladar Fleischmann Faculty of Engineering decided to advise an undergraduate student in a promising, short-term study.

But as we all know, the only thing you can count on in life is that everything changes: “The purpose of the study was to show a difference in damage to liposomes (microscopic spheres filled by fluorescent fluid and surrounded by a membrane, used in medicine and in scientific studies of biological membranes) by a nanomatter called MnO2, produced in various structures,” explains Dr. Zucker.

“In the past, we’ve shown a fluorescent fluid leak (i.e., liposome damage) was dependent on the surface of the nanomatter, and this time we wanted to show it also depended on its structure. But… research has its own rules – we couldn’t find the kind of damage we were looking for. Right as we were about to give up on the study, we took the system to a fluorescence microscope, where we saw that the liposomes and the nanomatter interact in a way we’ve never seen before in this context: the liposomes envelop the nanomatter, but remain whole, intact spheres without leakage! It was like a miracle of light.”

“Many times unexpected discoveries surprise us.” Dr. Zucker in the lab

A star (re)born

For Dr. Iair Arcavi, of the Department of Astrophysics at the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, a routine evening of surveying space through a robotic telescope led to discovering a brand new phenomenon: the resurrection of a star.

“A few years ago, we came across a ‘star that didn’t want to die’ and kept exploding again and again,” Dr. Arcavi says. “Every night the telescope would find lots of new things, most of them uninteresting. Even with this supernova (which is a star that exploded), we initially thought it was uninteresting, because when the survey first caught it, it was in the dimming stage, and we thought we’d missed the interesting part. We noticed for weeks that the supernova was starting to get bright again, which is something that shouldn’t happen, so that piqued our interest and made us follow the supernova with additional telescopes.”

“Many times unexpected discoveries surprise us.” Dr. Zucker in the lab

A star (re)born

For Dr. Iair Arcavi, of the Department of Astrophysics at the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, a routine evening of surveying space through a robotic telescope led to discovering a brand new phenomenon: the resurrection of a star.

“A few years ago, we came across a ‘star that didn’t want to die’ and kept exploding again and again,” Dr. Arcavi says. “Every night the telescope would find lots of new things, most of them uninteresting. Even with this supernova (which is a star that exploded), we initially thought it was uninteresting, because when the survey first caught it, it was in the dimming stage, and we thought we’d missed the interesting part. We noticed for weeks that the supernova was starting to get bright again, which is something that shouldn’t happen, so that piqued our interest and made us follow the supernova with additional telescopes.”

A supernova exploding far, far away

“Usually, when a star explodes, the light intensity goes up and down and eventually disappears after a few months. In our case, the light intensity went up and down, then did it again and again, for a total of five times over two years. What surprised us even more was when we discovered that this star actually exploded in 1954, and after a star explodes, it’s not supposed to explode again, because the explosion destroys the star. To this day no one’s been able to explain it, and we haven’t seen a similar event since.”

A supernova exploding far, far away

“Usually, when a star explodes, the light intensity goes up and down and eventually disappears after a few months. In our case, the light intensity went up and down, then did it again and again, for a total of five times over two years. What surprised us even more was when we discovered that this star actually exploded in 1954, and after a star explodes, it’s not supposed to explode again, because the explosion destroys the star. To this day no one’s been able to explain it, and we haven’t seen a similar event since.”

The sky is full of surprises: Dr. Arcavi and the Hawaii observatory

Two for the price of one

Have you ever looked for a solution to a problem, only to solve an entirely different problem along the way? That’s exactly what happened to Prof. Noam Shomron of the Sackler School of Medicine.

“We wanted to develop a way to identify a specific disease, but along the way we discovered more options, so we made those additional targets of the research,” he says. “We tracked thousands of pregnant women, to characterize blood molecules that can be early markers of preeclampsia, a condition that can only occur after the 20th week of pregnancy. Not only did we find those molecules, we also managed to characterize other molecules, that could be an indicator of gestational diabetes.” (There’s no connection between the two conditions, except that they both occur during pregnancy.)

“What’s exciting about this story is that there’s still no way of identifying, in the first trimester, using a simple blood test, problems that can occur in the second or third trimester. But our discovery will allow simple blood tests to be developed to identify both conditions, which will then lead to preventative measures at an early stage, and ensure the wellbeing of both mother and baby.”

The sky is full of surprises: Dr. Arcavi and the Hawaii observatory

Two for the price of one

Have you ever looked for a solution to a problem, only to solve an entirely different problem along the way? That’s exactly what happened to Prof. Noam Shomron of the Sackler School of Medicine.

“We wanted to develop a way to identify a specific disease, but along the way we discovered more options, so we made those additional targets of the research,” he says. “We tracked thousands of pregnant women, to characterize blood molecules that can be early markers of preeclampsia, a condition that can only occur after the 20th week of pregnancy. Not only did we find those molecules, we also managed to characterize other molecules, that could be an indicator of gestational diabetes.” (There’s no connection between the two conditions, except that they both occur during pregnancy.)

“What’s exciting about this story is that there’s still no way of identifying, in the first trimester, using a simple blood test, problems that can occur in the second or third trimester. But our discovery will allow simple blood tests to be developed to identify both conditions, which will then lead to preventative measures at an early stage, and ensure the wellbeing of both mother and baby.”

Professor Shomron talking about his accidental discovery at an “Atnahta” event at TAU

Professor Shomron talking about his accidental discovery at an “Atnahta” event at TAU

Prof. Israel Finkelstein at a TAU dig in Megido

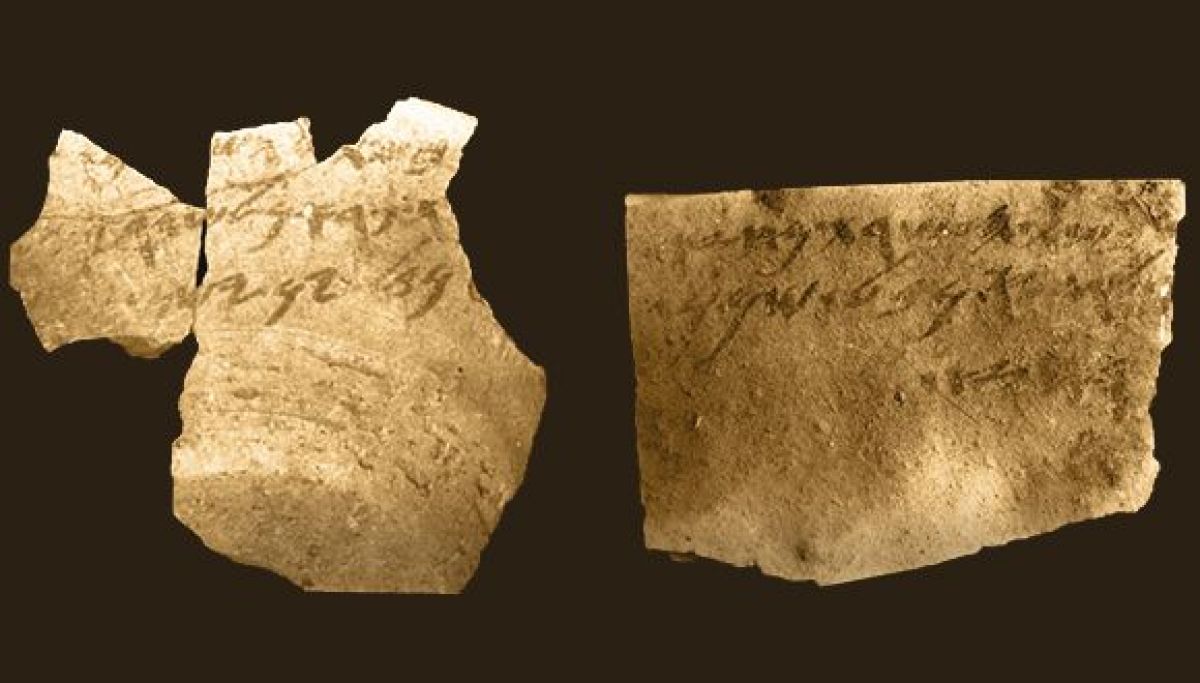

“The innovative technique can be used in other cases, both in the Land of Israel and beyond. Our innovative tool enables handwriting comparison and can establish the number of authors in a given corpus,” adds Faigenbaum-Golovin.

The new research follows up from the findings of the group’s 2016 study, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judah a century and a half to two centuries later, circa 600 BCE. For that study, the group developed a novel algorithm with which they estimated the minimal number of writers involved in composing ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad. That investigation concluded that at least six writers composed the 18 inscriptions that were examined.

“It seems that during these two centuries that passed between the composition of the Samaria and the Arad corpora, there was an increase in literacy rates within the population of the Hebrew kingdoms,” Dr. Shaus says. “Our previous research paved the way for the current study. We enhanced our previously developed methodology, which sought the minimum number of writers, and introduced new statistical tools to establish a maximum likelihood estimate for the number of hands in a corpus.”

Prof. Israel Finkelstein at a TAU dig in Megido

“The innovative technique can be used in other cases, both in the Land of Israel and beyond. Our innovative tool enables handwriting comparison and can establish the number of authors in a given corpus,” adds Faigenbaum-Golovin.

The new research follows up from the findings of the group’s 2016 study, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judah a century and a half to two centuries later, circa 600 BCE. For that study, the group developed a novel algorithm with which they estimated the minimal number of writers involved in composing ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad. That investigation concluded that at least six writers composed the 18 inscriptions that were examined.

“It seems that during these two centuries that passed between the composition of the Samaria and the Arad corpora, there was an increase in literacy rates within the population of the Hebrew kingdoms,” Dr. Shaus says. “Our previous research paved the way for the current study. We enhanced our previously developed methodology, which sought the minimum number of writers, and introduced new statistical tools to establish a maximum likelihood estimate for the number of hands in a corpus.”

“But these studies did little to tap into the inner worlds of children, which really can only be accessed through self-expression in the form of art or self-reporting, independent of parental intervention, which is the route we took in our study,” Prof. Zaidman-Zait says.

“But these studies did little to tap into the inner worlds of children, which really can only be accessed through self-expression in the form of art or self-reporting, independent of parental intervention, which is the route we took in our study,” Prof. Zaidman-Zait says.

“Our study makes a valuable contribution to the literature by using an art-based data gathering task to shed new light on the unique aspects of the relationships of children with siblings with intellectual disabilities that are not revealed in verbal reports,” Prof. Zaidman-Zait concludes. “We can argue that having a family member with a disability makes the rest of the family, including typically developing children, more attentive to the needs of others.”

The researchers hope their study, supported by The Shalem Foundation in Israel, will serve as a basis for further research into art-based tools that elicit and document the subjective experience of children.

“Our study makes a valuable contribution to the literature by using an art-based data gathering task to shed new light on the unique aspects of the relationships of children with siblings with intellectual disabilities that are not revealed in verbal reports,” Prof. Zaidman-Zait concludes. “We can argue that having a family member with a disability makes the rest of the family, including typically developing children, more attentive to the needs of others.”

The researchers hope their study, supported by The Shalem Foundation in Israel, will serve as a basis for further research into art-based tools that elicit and document the subjective experience of children.

Working together: members of the delegation with locals from the school in Babati district

Working together: members of the delegation with locals from the school in Babati district

Smiles all around: Julius and his family with members of the delegation

At the biggest, most central school in Babati district, where the largest system was about to be installed, the delegation was greeted with an enthusiastic welcome. Knowing that soon every student would be able to enjoy clean water was exciting for the children.

Smiles all around: Julius and his family with members of the delegation

At the biggest, most central school in Babati district, where the largest system was about to be installed, the delegation was greeted with an enthusiastic welcome. Knowing that soon every student would be able to enjoy clean water was exciting for the children.

Hope and excitement: the delegation is recieved by the young students

Hope and excitement: the delegation is recieved by the young students

At the principal’s office

The first order of business for the delegation was teaching a group of boys and girls from local Scouts how to help with the construction and then later on how to maintain the systems. “The idea is not just to build a system, but to work collaboratively with the community, which includes education and instruction, which will lead to long-term results,” Natalie explains.

At the principal’s office

The first order of business for the delegation was teaching a group of boys and girls from local Scouts how to help with the construction and then later on how to maintain the systems. “The idea is not just to build a system, but to work collaboratively with the community, which includes education and instruction, which will lead to long-term results,” Natalie explains.

Left: local Scouts learning the new system. Right: children from the school using it to get clean water.

The construction process included installing gutters, cleaning the water tanks and preparing the infrastructure. In one of the schools, where systems had already been installed in the past, the delegation had to replace containers, destroyed by elephants that came in search of water, and build anti-elephant concrete walls around them.

Left: local Scouts learning the new system. Right: children from the school using it to get clean water.

The construction process included installing gutters, cleaning the water tanks and preparing the infrastructure. In one of the schools, where systems had already been installed in the past, the delegation had to replace containers, destroyed by elephants that came in search of water, and build anti-elephant concrete walls around them.

While the systems were being installed, the delegation members taught the students about proper use of the system and “water discipline”, and in return the students taught them local songs and dances.

While the systems were being installed, the delegation members taught the students about proper use of the system and “water discipline”, and in return the students taught them local songs and dances.

Singing while you work: two members of the delgation with young students

When it was clear that the work was progressing quickly and efficiently, the delegation decided to visit local families and get to know the community. “We started asking them questions about their daily lives and their needs,” Natalie says. “We realized that in addition to building the systems in schools, we also want to think of a home solution. Most people here live in extended families, sometimes numbering up to 50 people. So, a solution for one family can spare them a walk to the nearest water source, which can take hours, and also give them clean water, as opposed to reservoirs that are very polluted. Our challenge was to think of a simple, creative and inexpensive solution, using local materials, so we could easily distribute and duplicate it, and they could easily maintain the systems.”

Singing while you work: two members of the delgation with young students

When it was clear that the work was progressing quickly and efficiently, the delegation decided to visit local families and get to know the community. “We started asking them questions about their daily lives and their needs,” Natalie says. “We realized that in addition to building the systems in schools, we also want to think of a home solution. Most people here live in extended families, sometimes numbering up to 50 people. So, a solution for one family can spare them a walk to the nearest water source, which can take hours, and also give them clean water, as opposed to reservoirs that are very polluted. Our challenge was to think of a simple, creative and inexpensive solution, using local materials, so we could easily distribute and duplicate it, and they could easily maintain the systems.”

Sometimes the villagers are forced to drink polluted water

Sometimes the villagers are forced to drink polluted water